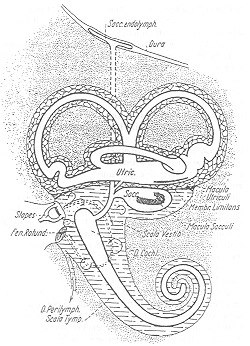

A figure from G. Békésy's article, published in 1935.

Fizikai Szemle honlap |

Tartalomjegyzék |

Georg von Békésy

(1899-1972)

I was born in Budapest 1899. Unfortunately, I was not healthy during the first period of my life and our house doctor suggested since he knows of no medicine which can cure me maybe a change in climate will do it. He was right because in Munich I became again completely healthy. Unfortunately, after this story was told to me, I started to mistrust all medicine and I did it in my whole life. It is a sad thing to be in later years as a scientist involved in medicine and not to trust it.

Munich at that time was one of the centers of culture. It had already in 1900 the first automatic telephone, which did not work too well, but it was an automatic telephone. There were many other things which were completely modern, like collecting garbage in three different holders, one for food, second for paper, third for dirt. Some things many cities copied later. But one thing that they couldn't really copy was the wonderful attitude and gaiety of the Bavarian people at that time. During my whole young years, I was surrounded by' artists and with people who were extremely interesting. My father was able to keep many friends. The exchange of ideas, which in many cases I wasn't able to understand; were still making on me a deep impression. At home we talked Hungarian but in the school I had to talk German and therefore, immediately there were some difficulties because my German had a bad accent. But I still remember now in my old years that there is a way of living which is pleasant and interesting at the same time. You can't find it everywhere but at some places you can still have it, and it depends to a large degree on the circle in which you are moving.

From Munich my father went to Constantinople. Constantinople was a most beautiful place at that time. We lived in Minor Asia and I never will forget the sunsets on the Bosporus. Politically, it was the worst place in the world. There were constant fights, killing and murder. It was the time when Ataturk started to develop his power. Nobody was safe on the streets, but still the Bosporus and all its surroundings on the Marmara Sea were the most spectacular view. In Constantinople I went to a French school and I practically forgot all the German I knew. I became slowly interested in French and I admired very much the power of the French language which was able to express ideas in an absolutely correct and precise way. French was, at that time, the speech of the society and everybody did speak French. At that time few people did know English. I hardly knew it existed. However there was no question about the fact that the whole Ottoman regime was declining in a very rapid way. As a young boy I just couldn't understand why a country should decay after it had such a big reputation and power. Even today, I have the same problem not with Turkey but with other countries. On the end in Constantinople there was a revolution and we had to leave Constantinople to my biggest regret, in a hurry. From there we went to Switzerland. It was exactly the contrary to Constantinople. The mountains were beautiful but the whole country was so organized and so well developed that there was nothing anybody could find wrong.

The Swiss schools were just excellent. I am very thankful to my father that he immediately recognized that the public schools were much better than the private schools. It was in Switzerland where I learned how efficient teaching can be if it is done correctly and if it is done by teachers who really love their profession. I am still thankful to the teachers I had in Switzerland. They were simple people completely devoted to their students. Switzerland at that time had three languages, French, German, and Italian, and it was quite obvious that everybody who stayed for a while in Switzerland picked up all the three, at least to a certain degree. I mixed all the three with Hungarian and, as a consequence of that there is no language that I really can speak correctly. Furthermore besides the precise German you had to speak the Swiss local language, Switzerdeutsch, which is quite different. It is maybe a mixture between German, Swedish and Danish. The Swiss-German is a leftover from the 30-year old war when Switzerland had troops of many countries.

Since I never was too healthy, I was not interested in the mountain climbing but I liked very much the libraries: The libraries were excellent and I made friends with the librarians and they really helped me to go ahead. The Swiss schools, at least the private schools, had one very' extraordinary feature. It was the so called mobile class system. Everybody could select the topics he was interested in, and then go through them with a higher speed as the general class would do. I picked at that time mainly physics and Latin as my field of interest and I finished these classes very fast. After that, there were some other things that one had to learn like orthography of German and French. What I didn't like at all was the history of literature. I didn't like general history because I had the feeling it was written in an incorrect way. In my father's library, I found the large handbooks of history like Schlosser and they told very different things than my text books.

Schlosser gave always the reasons for the wars, or at least he tried. He put down the economical situations, and how many soldiers were in the battle, and I could see that there is absolutely no end of fighting in this world. It will go on probably tilt the end of my life and this feeling was correct as far as I judge from now. There were many optimists in Switzerland who said they will form a type of United Nations or something like that, but I never believed in that because it was never really clearly written out that the reasons for the war were mainly business competition.

In Switzerland you had to pass the so called Maturiätsprüfung, and that is a very difficult examination since it is government controlled. I passed it successfully and then I had free time for about a half year since it was not permitted to attend the university before the age of eighteen.

My impression today is that the half year when I didn't have to go to school was maybe the most important time of my life. During that time I wanted to learn mechanics and I simply went to a workshop. They taught me how to file, how to use the hacksaw and how to use a turning lathe. The mechanics are old, very precise gentlemen in Switzerland, and they didn't like me too much. But, sooner or later we developed a sort of friendship because I knew a little more mathematics than they did and, therefore, we became dependent on each other. It was bad when I had to give up this unprofessional situation. Since I didn't have to work during the half-year and I found out that it is possible to survive, at the university without listening to too many lectures, I decided to have only three lectures per week and to spend most of the time in the laboratory. At most universities this is not permitted, since they want right from the beginning a well balanced education. My feeling was, that this free situation gave me the opportunity to balance my problems in which I was involved in the library.

I started in the beginning with chemistry, which was exciting at that time. I had always the impression that chemistry will change in a few years and it will be more a part of physics and I slowly went over into physics without really noticing it. Physics was hard to understand so I shifted into theoretical physics and into mathematics. It was a logical development: and I never regretted it. Nobody should regret to study mathematics in his younger years because that is the only science which is really disciplined. My teacher in the Swiss school always told me that one should learn Latin, because Latin is the only logical language and it starts to discipline our memory and our way of thinking. I agree with him completely and I liked Latin reading since it is so simple and precise as compared, let's say, to English. I almost became a mathematician but the problem with mathematicians is that it is extremely difficult to get a job. In Switzerland, only the insurance companies applied them and I found that life insurance mathematics is pretty dull. The second possibility was to wait tilt some professor of theoretical physics died. The question if I should stay in mathematics or not was solved in a simple way because I was drafted into the Army. After 1918, when the war was over and I returned to Switzerland, it was impossible for me to concentrate myself on subjects like four dimensional geometry or relativity theory, that was at that time of main interest. So I decided I had to take up something more simple and I went into experimental physics.

Experimental physics was at that time quite simple but developing. We had already difficult and complicated equipment in the field of optics and therefore, I decided to work in this field. I did my thesis in experimental optics in Hungary. I used what is called today Interference Microscopy, and I made a mistake not to publish it. The final Ph.D. I made at the University of Budapest since my father told me everybody should make his Ph.D. in the country of which he is a Citizen. He was correct, since in most countries they don't accept the Ph.D. of a foreign country. This was a consequence of the war situation.

After I got my Ph.D., I just didn't know what to do. There is nothing worse than the situation after having finished the school on the university, since nobody wanted my knowledge. I had an extremely difficult time in looking around till I realized that everything I learned from the university had a very limited value since it was not possible too apply it. In my despair, I finally decided I will just look around for a good laboratory, and after I found one, I will work there for nothing as a beginner. This approach worked fine. I found out that the only laboratory in Hungary which was well equipped after the war in the year of 1920, was the Hungarian Government Communication Laboratory. The reason why it was well equipped was very simple. The cost of a cable through the whole country was extremely expensive, and therefore, the Government decided that they were willing to spend 1% of the price for research and for measuring equipment so that the cable could be tested properly. We used this test equipment seldom, but I used it for many, many years to come. The system worked very well, since every time there was in investment in cables, I got about 1% of it.

The Hungarian government research office was very well organized. In the Laboratory, there were about 100 people with one director, who was an engineer. He was friendly and interested in nothing else than to make everybody working successfully. At that time, it was so that we had to work for the government precisely from 9 till 1 pm, so that the afternoon was almost completely free. This way, I was able to do many of the research without any interruptions. Every time in the morning I cleaned up all my anatomical problems and I started with official work. But during the whole evening and maybe late into night, I could do all my research.

The reason why I got interested in hearing was a very simple thing. The government asked the question, "What will be the future development of telephone communication?" There was a possibility that the long distance cable will improve, or the telephone or the microphone or the switchboard. Their question was where should they invest their money? My opinion was they should invest the money in that part which is the least developed so a small amount of money could produce a large improvement of the whole transmission system. Everybody agreed with that concept and I started out to test how could the quality of the different parts tested. It turned out in very simple measurement that the microphone is about the poorest equipment in the whole line and therefore the financial support should be given to research which may improve it.

My test was very simple. I plucked the telephone membrane and determined the resonance frequency and the damping of the membrane. By comparing these two numbers, the resonance frequency and the damping of the membrane with the situation found on the eardrum, the membrane turned out to be very poor. The fact that the eardrum was so much better constructed in any respect than the telephone membranes gave me a point to prove that the next development should be the microphones. Having said that, naturally my interest went from the middle ear into the inner ear, and sooner or later the whole research became anatomy. Since I had only a diploma for physics, I had very big difficulties to get permission for receiving some heads of cadavers that I could dissect. Many people were very unfriendly in the beginning and I don't hesitate to say that my own uncle who was university professor for anatomy, was of the opinion that anatomy should be only done by M.D.'s and not by physicists.

Fortunately the solution was simple because in every anatomical institute there are two doors, one in the front where the professors and students walk in and then a back door where the cadavers are taken in and out. I found out that by going through the back door, I could get as many heads as I wanted. The only problem was how to take them to the government research laboratories mechanical workshop. Later I found a way how to make friends to support me. On the end, the anatomical institute's professor agreed also and helped me to get all the material that I needed. This permitted me to dissect inner ears of not too old cadavers and that gave the base for all my later work. Without doing this, I would have had a completely wrong concept of the real functioning of the ear. I am very thankful to all the people who helped me in that respect. I am especially thankful to one police officer who one day told me that he could have arrested me any time for murder since I carried a human bead in my briefcase.

My research in anatomy was very much disliked by the mechanics. They had to always clean the drills, etc. from blood and bone dust. So to avoid that, I developed a method where the tissue was put in a tank which was filled completely with water or physiological solution. This physiological solution was flowing very slowly with a constant speed from the right side to the left side of the tank. The speed was adjusted so that it didn't disturb any possibility to watch under a water the specimens with a microscope. It had a tremendous advantage because any piece of tissue that was lifted up just had to separate from the tissue and by letting the forceps loose the little piece would float by itself slowly away to the left side so the field of view was always clear. The same thing did hold for bone dust.

I was probably one of the first who used constantly high speed drills to drill out the cochlea and to investigate it that way. By doing so the most disturbing thing is the bone dust. But if the whole temporal bone, which is about the hardest bone of the human body is placed under water, then after drilling immediately the whole bone dust will flow away just like a cloud, so that in a few seconds, the field is again clear. After this development, the whole anatomy of the ear was so standardized that there were no more difficulties in doing it. We had a special drill which cut out the temporal bone from the bead so that a cylinder of the temporal bone was obtained which fitted exactly in a metal ring. This metal ring was screwed in the different equipments and in a few seconds, so that it was possible to carry out all the different measurements by screwing in the same ring in the different ready standing equipment. This way, it was possible to see how the different parts of the basilar membrane vibrate and a travelling wave was found.

Travelling wave hearing theories were suggested in different ways but nobody had ever seen a travelling wave in a human cochlea. Naturally, the first suspicion was that the cadaver's elasticity must be very different from the elasticity in a living human. This could be very easily disproved by having a cat or a guinea pig dissected under anaesthesia and then watching the vibrations of the basilar membrane in the living animal. After killing the cat by an overdose of anaesthetics it was easy to show that the vibration pattern in the cochlea didn't change at all during death and it was even possible to keep it that way for many, many hours if the temperature of the room was decreased to about 5 centigrade. It was clear from this test that we could investigate the mechanical properties of the tissues of the middles ear and the inner ear in preparations and we do not need to do it on living animals. That simplified to a very large degree the situation. Naturally, if we want to go to real precise details, we have to always check in the living.

The travelling wave concept was new and it showed a very big difference between the concepts which were used. It turned out that for certain frequencies, let's say for high frequencies, the maximum of the travelling vibrations was near the entrance to the inner ear and for low frequencies, it was far away. This way, it became evident that there is mechanical discrimination of frequency done in the inner ear.

One of the main questions which was next to be settled was the problem, how is the ear so sensitive? My opinion was that the ear can only be so sensitive if it is not the energy of the sound which is transformed into electrical energy of the nervous system. But sound energy only triggers a certain process and this process supplies the energy. To prove that a triggering system works, I was able to show that the energy input to the cochlea is much less, hundred and thousand times less, than the energy output through the auditory nerve fibers. Settling this, it was clear that we have now to investigate the triggering process in hearing. This process is still under discussion because it is one of the Basic phenomena of living tissue, how a small stimulus can produce a large reaction from an energy reserve. Because the ear doesn't need energy, it is not an energy transmitter, but it is a triggering system, just like an amplifier.

The next step in the investigation was how is it possible to investigate the nervous system? Is the nervous system similar for all the sense organs, or is it quite different? It turned out in the last experiments that I did that there is a very close relation between the nervous systems of different sense organs and it is almost so that by knowing one sense organ, it is possible to predict many phenomena in the other sense organs. This is the main issue of my research today. To do this type of research, I had to leave Europe after the World War II.

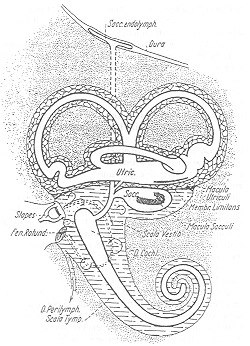

A figure from G. Békésy's article, published in 1935.

In Hungary, unfortunately the situation became unpleasant. I was made Professor of Experimental Physics and I had a large department and many students. I liked very much the students and I liked to a certain degree to teach and I liked the workshop and I liked to see the students learn. I learned myself from mechanics in the workshop and I wanted to give them the same opportunities. Unfortunately, there are rigorous rules that you have to keep at the University. I had first-class assistants who helped me and it was my biggest pleasure to see that after two years, my laboratory at the University ran smoothly. I had two laboratories, one under the Government, and one under the University and I had one laboratory with a doctor who helped me to solve some problems which couldn't be done neither on the university nor at the government laboratory. It was this period in my life which was the most productive. I worked from morning to noon one place and in afternoon and the evening I was in the other two laboratories. I had many collaborators and we had practically very little to discuss except science.

After a few years later, the war started and the government took away many of our free time. I was forced to do government jobs which really stopped the research in hearing. Everybody did so and we had to do it. Hungary had no platinum or ore at all, so questions came up how can we replace in a telephone relay platinum with some other metal. I think we were some of the first ones who used mixtures between tungsten and gold and tungsten and silver and so on. That was a new approach and the question how a contact should be made, so that it does not burn out and still is able to carry large currents was a very interesting question. After a certain time, it was quite clear that Hungary will be occupied by the Russians. I don't want to talk about my experiences during the siege of Budapest. It lasted a long time and nobody was sure if he will survive. Most of my friends were killed during that period, my mechanics were deported to Russia and everything became unproductive and there was no way to continue research. At that time I accepted an invitation to go to Stockholm. Stockholm had no war since 150 years and they lived in a very peaceful world. I accepted that invitation and was able to do some research. I developed there an audiometer. The Swedish were very friendly, especially the engineers. In spite of the fact that my research field didn't belong in the field of engineering, they helped me so much that I was able to have hundreds of patients examined at the Technical University and I am always thankful to them for that because that gave me a chance to improve and not to forget the research I started before.

After a year, it turned out that Sweden was in a bad economical position and they had absolutely no money to give me a position so that I would be able to stay in Stockholm. Therefore, I accepted an invitation to Harvard and I spent 17 years at Harvard University in the psycho-acoustic laboratory. This was a highly developed laboratory. It was a leftover of the war organization with a strict organization, strict rules and good work was done. As time went on, there were too many other problems coming up and there were too, many discussions. The American system is very different from the Hungarian system and I have the feeling the Hungarian system achieves the same thing in a much simpler way.

In the United States it is custom to discuss the questions and there was always a staff meeting where all the questions were brought up. These staff meetings could last many, many hours. There were always at least five or ten people involved and very seldom it happens that they made a clear decision on one subject. The Hungarian style was so that there were small little laboratories. Everybody got his own little empire and he could do in that empire what he wanted to do. He got a certain amount from the budget and no questions were asked further. Everybody was able to realize if somebody didn't work but, in general, they all worked. In spite of the fact that most Hungarians are very comfortable and they liked the good life, they all found out that to do research is a real pleasure, and slowly they became enthusiastic researchers who were willing to spend nights sometimes in the laboratory even without any salary increase. In the United States, it was very different because most people worked for the dollar. There were some exceptions, but most of them were adjust that way. Under this situation, most of them were much interested to get results quick. We never had in Hungary that problem because we could work on a problem so long as we wanted, but one thing was very important to make sure that no mistakes were done.

There was no question that the laboratories in the United States were very much better equipped than in Europe. Too much equipment can be, however, something that hampers scientific development. I had the feeling that if there is no equipment present, everybody is forced to simplify his ideas in such a way that the experiments become simple. If there is too much equipment available, he can attack any experiment immediately since all the difficulties will be overcome by putting more money in the equipment. In the long run, some of the equipment becomes so complicated that it is difficult to see how all the parts interact.

In the United States, I made progress in the investigating of the cochlea mainly since I was able to show how the cochlea is supplied with energy. I could show how the sound doesn't produce the energy which goes along the nerve fibers to the brain, but it was a trigger action. Further it was possible to clarify many questions, especially concerning the similarity between the skin and the inner ear.

In the last two years, I went to Hawaii. Hawaii is far away from Cambridge. It is absolutely different, it is a new world, it has its advantages and many, many disadvantages seen from the pure scientific point of view. Life is just too beautiful. I had the feeling that by air conditioning everything, I will have no problems concerning my working ability. That is correct, but you have to air condition in that case not only your own rooms, but the rooms of all your co-workers and not only in the laboratory but in the homes also. Since this is not possible, the real scientific output is less as it was on the Mainland. But on the other hand, I had the opportunity to see things that I never had seen before, like fishes and insects and lizards in free surroundings. It can improve the quality of my work in a different way.

Today we have a very large increase in population and, therefore, the problem comes up what should the young people learn, how should they do it, and for the older people, especially the professors, how should they teach? I think in the future, the different countries will still compete with each other and, therefore, the solution to this problem is of outstanding importance because the country which will be able to teach the young people the best and easiest way will probably in the long run control large sections of this world's thinking, and commercial possibilities. For this reason, I was always looking back from whom did I really learn something. Did I learn most of my useful things in the school? Did I learn them from the universities, or did I learn them during my life from private experiences?

I always had the impression that from the point of view of knowledge, it is very good to be a Citizen of a small country, because in a small country, right from the beginning, we probably will have to learn different languages and we have to look around to all the other countries which surround you. Therefore, we get more awakened and more interested in things which go around us and are not so much self-centered, as people who are grown up in a large country where they can work and live for their whole lives knowing only one language and reading only a few books. Otherwise, I don't think that it is good to be a Citizen of a small country, since they are always controlled by larger countries.

I think it is a quite natural assumption of a young child to hope that there is a sort of funnel, which simply will funnel into him all the knowledge of the older people. Such a dream of a funnel was already well known in Nürenberg in the 16th century. At that time, Germany had the first real mass production in mechanical equipment but, they didn't have such a funnel.

It is interesting to realize how difficult it is already for mother to transmit her experiences to her daughter. It is even more difficult to give good advice to her son. I have the impression that the troubles of our world start already with the fact that we cannot use and we cannot apply the experiences of our parents. Somehow we need our own experiences since they are so dramatic and so painful that we will remember them for a long time. Nevertheless, everybody learns from his parents a large amount. I never will forget the small walks that I had with my father. We had talks about all the problems in the world and we simplified them and summarized them in such a way that I really was able to understand better what I have to expect when I am grown up. I liked to read the encyclopedias and their facts. The encyclopedias helped me to realize that if we fill up our head with facts, we are still not doing anything. So, sooner or later, I came to the conclusion that the encyclopedia is just not the way to learn science, because even the best articles that are written give only a summary; hut from that summary it is quite a big way to start to use what is in that summary. Since facts are not of outstanding importance, I came to the impression that what the teacher can really do is nothing else than to point to certain directions. From there, we can use our own brain. So a teacher really doesn't teach us too much. He should really teach only the love to work and a sort of triggering action which will help to keep us interested in certain fields. I looked always at my teachers in this way, and I didn't want to learn from them facts. I wanted to find out the method how they worked. The moment the teacher doesn't teach methods of research, especially in the university, he is not able to give profitable ideas to the students, because later the facts that the students have to use in their work are in general different from the facts he taught. But the only thing that stands out and will stay for the whole life is the method of working. This is the reason why I was interested in the method only. There are certainly many difficulties in teaching methods. It is difficult to test a student if he knows the methods of thinking. It is very easy to test him about facts, and to grade him. Therefore, the whole system of grading produces a problem today, since, we are more overloaded with facts with little value than 20 years ago. Naturally, there are some Basic facts that everybody has to learn and know.

I liked very much the universities in Switzerland, mainly because nobody was ashamed to show what he knows and what he did not. There was no pressure. If you didn't know something, you always could say openly I don't know and that didn't take away anything from your importance. This way, it was possible to see how some people think and what was their failure. One of my most important experience in my life was that I found out that making a mistake, even a large mistake, is not always completely lost work. If somebody is bright enough, and he made a mistake, he always can learn from the mistake to improve his method of working. Certainly the facts are lost, but I never was very unhappy as many people were if they made a mistake. By having learned this from some of my professors, I came to the conclusion that I can stick out my head and take a risk. If we want to make a discovery, we have to take a risk, since everything new was discovered by accident or by the fact that somebody took a chance and went ahead when there wasn't 100 percent safety for the solution.

Today, we are unsuccessful because there are so much request for progress reports and five year plans. In science, projects in general do not lead to big discoveries. We can only make a progress report on facts and but not of a method of thinking. Therefore, one thing that was so valuable I learned in Switzerland was the fact that I was not ashamed of my mistakes at all. There were some mistakes I even liked, because they led to really new problems. I never will forget a lecture in chemistry. The professor who gave the lecture at the University of Berne, wasn't too much liked. He was a refugee and even in Switzerland, a refugee knows in general that he is a refugee, and he was always a little on the defensive side. I sympathized with him because I was a foreigner also. But most of the students didn't like him because he never talked with anybody. But he made wonderful experiments and one day he wanted to show during the lecture, how to make from sir ammonium and then from it a fertilizer. It was a complicated procedure, developed for big factories, and not for the laboratory table. After he explained the whole process, he switched on the equipment and for reasons nobody knows, the whole equipment blew up in one second. There was practically not one bottle left unbroken after that explosion and we were running around to see if anyone was hurt. Fortunately, nothing happened.

I had the impression that after this failure, the professor will show us the experiment in the next lecture, or maybe give it up. His whole attitude was absolutely different. He simply told us that he was very sorry about this accident, and at the same time, he started to rebuild before us the whole apparatus. I learned more from him about chemistry during the next hours than from many, many lectures I listened. We could see how he worked, how he put together the different parts, all the while thinking where he could have made the mistake. The bells rang so the lecture hour was over, but he didn't stop working even after the bell rang the second time and the other lecture started. We were so fascinated we did not leave. In about two hours, he had again the apparatus ready and it worked. From this you can see that it is possible to learn from small items important methods.

I liked the Swiss universities for one other reason. The Swiss universities tolerated so called old students. They were students who stayed in the university for ten fifteen years. I learned very much from these students because they taught, not because they had to teach, but they taught for pleasure. Besides teaching me chemistry, they taught me the professors' habits also. That made life extremely simple. They were a sort of catalyzer in the whole student life. They were, in general, not geniuses at all, but they knew how to handle important small things.

If you are a student today in the university, just as it was 40 years ago, the problem was what to do and what to learn. Already 40 years ago, the number of facts and the number of possibilities were so large that one of the most disturbing problems was the choice of the subject. I started the wrong way, with chemistry, from these I went to physics, and finally I was interested in astronomy. After I went through that whole spectrum, I had a very difficult time to find out what shall I do. In this whole situation, the lack of a program blocked me and inhibited my thinking and working. At the end, I became definitely passive instead of being active that everybody expects from a young student. Maybe what changed my attitude was the French proverb saying, "you start to get hungry during eating." Therefore, I came to the conclusion we just have to start to work and during work, we will find a way how to get ahead and even a goal. It is only the start which is difficult. I think there are so many goals and so many possibilities that it is not important which goal we pick. The important thing is that we start to work, and after that start the next question is the method. The biggest handicap that modern students have is the start. I had many times in my life to fight the difficulty of the start. I had it at the Swiss university, but later on after my laboratory was destroyed twice as a consequence of the two wars in Hungary. I remember very well when in the second war, after the first bombing, we left the shelter and de found the whole laboratory almost completely destroyed. It was a difficult decision to start and do the things that can be done, so that later we will try to get back to the problems we were working on before. Here again, the start was very effective. Once this big hurdle was overcome, my whole nervous system quieted down. I simply wanted to make one simple experiment. In spite of the fact that we were bombed over and over again and the destruction went on and on, everything was dust, we couldn't read because the eyes burned from the dust, we still went on and on. If somebody would ask me today who gave me that force, I would say it was the professor who after his chemical apparatus blew up, started right immediately fresh.

There are whole nations who have difficulties in starting. I just can't understand that because if only some of these people would give up to wait for something which comes from outside, and start to work with what they have, I am pretty sure sooner or later they could puff the whole nation in a working group. Work is already a pleasure even if we don't have always success. If we have just a little hope that you will have success, it feels good. It is the only pleasure which is rewarding in the long run. Maybe you don't become famous during your lifetime, but I am sure if you did a good job you will become known later, it just works that way. There is a need for good solid work and they will always pick it up sooner or later.

I always had the impression that I owe very much to the engineers and the fact that I worked between the group of engineers. The engineers didn't speculate much what to do, they simply started to do it, anything that seemed to be reasonable. This is how Hungary was built up after many destructions. In engineering work the main interest was in the solution, and the first problem to be discussed, so practically all the sidelines were very quickly forgotten.

During World War II, we had in Hungary, in telephone engineering, a very difficult problem because Hungary was for many years in the period between the two wars and during World War II, shut off from metal import. Hungary had no platinum at all and practically very little copper. Without copper, it took almost no time to find out that it can be replaced by aluminum. Hungary had no known aluminum ores. Then under the pressure, so much bauxite was found, it could even export. And here again, it was the spirit of the engineering team which made it.

Another such question was that we had no platinum and couldn't make telephone relays with platinum contacts. As it is known, an automatic telephone has a million of relays to operate. I think we were the first ones in Hungary who simply replaced platinum with the mixture of tungsten and copper. It turned out that this new type of mixture was much better than platinum. Being pushed in one direction, can help to produce outstanding things if we don't give up.

Since my father was a diplomat, I had the chance to live and stay in many countries. From every country, I learned something different. It is surprising how many countries are leading in some specialty.

From Switzerland I learned that it is possible to outdo any competition by doing high quality work. I think the Swiss watch is the best example for that. I am immensely grateful to the Swiss watchmakers. They showed me many of the features that I used later by dissecting the cochlea. It gave me the feeling how important it is not to give up quality even if there is the pressure to produce in quantity.

At that time Hungarian universities enjoyed autonomy and inner freedom. Teachers were at mutually good terms with the students. This helped me to forget about everyday troubles which, though insignificant, made me lose quite a lot of valuable time. (I must, however, add that it is manly the older universities which are as fortunate as I just said; the younger ones are much more exposed to external influence, the main difficulties arising from the new style of ensuring financial support.) What I appreciated most in the happy years I am speaking of is the teacher-student interaction: the students rejuvenated me every year and helped me reassure many young people who had lost confidence and convince them that there are values worth living for.

In Germany I learnt to work hard and to love work for itself. There is always work to be done, but we have to do it ourselves if we want to enjoy it. Work rather than the dollars you get for it makes one happy, since the greatest satisfaction results from giving rather than getting something valuable.

Russia taught me that if a great nation sets to work, fantastic results may be expected. I never witnessed such fast progress as in this country. Their methods of organizing scientific research are truly remarkable.

In the United States, I tried to apply all my experiences gained elsewhere. A1 present, I am a professor of sciences related to biological sensing processes at Honolulu University. I have been here for three years and consider it to be the most interesting place I have ever been to. It is incredibly international, with Asian, Australian, American and European people living here, all of them mutually respecting each other. At the same time I had to realize how utterly different eastern and western ways of reasoning, working and expressing views and tastes are. These differences are wholly resistant to organizational efforts and even to great wars. It must not be forgotten that they took shape several thousands of years ago and still must be reckoned with. Maybe I am in a favorable position to recognize and understand differences, being an active collector of antique masterpieces of art. Yet, it took me many years to understand the very significant difference between the Chinese and Japanese ways of thinking.

Here at Honolulu we all know many cultures, each with its own specific history and its views on life. One might believe that they easily mix, since all of them thrive in the Pacific space. In fact, art history clearly proves that about 2000 B.C., China dominated this space - at least in cultural respects. All art of this epoch shows the characteristics of the Han dynasty. However, after the erection of the Great Wall, Chinese influence apparently ceased and on each island a specific culture developed. It is on the Hawaiian Islands that I realized the complexity of the world, the difficulty of understanding other peoples, even if we try to do everything to this end.

Scientific work here has been very interesting. My recent research relates to inhibitions and introduces a wholly new way of viewing the science of perception.

I have also experienced many surprises. For one, books may be found more easily in Honolulu, than on the Mainland, since libraries are very well organized here. On the other hand, many difficulties arise from the fact that here we never know what future may bring.

Many people have asked me what I would do if I had to start my life again. I am pretty sure that I would again choose scientific work. Some of my school mates became millionaires and have had very pleasant lives, almost without struggles, and were in position to buy everything that could be bought for money. Nevertheless, I believe in the need to fight or resist to make life interesting. They always envied me, I didn't envy them, in spite that I lost in my life three times everything I had. It is so that everything has advantages and disadvantages and the balance is often small. As far as I could see, it depends how we use the things we have. It is not the things that we have, but how we use them that is important. For instance, I enjoyed the small library that I had in the beginning more than the large private library that I have now. At that time, I knew practically every word in the books, now I have only a vague picture of the contents. Therefore, I would like to make my territory small, but have it under control.

From the different fields of science, I still would prefer medicine, because it gives the satisfaction to have reduced pain of people. Sometimes the idea that we saved lives doesn't occur during the research, but after the research is finished and we have the feeling in later years that we cannot produce more effectively as before the feeling having done something that is useful for humanity is very pleasant.

The second thing I would be interested in is the social relation between people. Ultimately, this is just as important as medicine. I am of the opinion that abnormality in many people is a bigger disease than all the well accepted diseases. These abnormalities are very small and are sometimes hard to detect but still they can ruin the lives of large groups of people.

Concerning studies, I would not learn Latin as I did, but I would replace it with mathematics. I would start to learn mathematics as early as possible. Mathematics and geometry are still the beat means to learn high level logical thinking. Mathematics is a language. If we don't learn it during our early years, you never will learn it correctly. Therefore, we have to learn mathematics right from the beginning. The fact hat many people don't like mathematics is a consequence that they started to learn much too late. It is very difficult to learn mathematics at an old age. We can't concentrate enough. But if we learned the beginning of the language in early life, then it certainly is something that will stay with us for the whole life. Again, it is not the knowledge of mathematical formulas that we have to learn. There are plenty of tables for formulas; but we have to learn the way how to get and solve the problems. Mathematics is the beat philosophy of all the sciences, including medicine and general philosophy, chemistry, physics, and even social sciences. There are people who think in pictures, and they should study geometry. I prefer geometry very much and a combination of geometry and mathematics can be very valuable.

I had the feeling the best way is to start with the difficult things right in the beginning and go from mathematics to physics, from there to chemistry and end up in medicine.

Many people think that after they finish the university, that is the end of their training. This is a mistake. I would spend much more time than I did to keep in contact with universities. Everything changes so rapidly' and is so difficult to follow once we lose the tracks.

When I was young, I was able to work all day, because it was so interesting. But it is quite sure that effective work needs a certain rest. It is very important for anybody to have a hobby - painting or sculpture - and I would combine it with science. I would learn sculpture, painting, or music as early as possible, paralleled with science so that in my hobby, I am not an amateur but I could reach a certain level which would satisfy me. It is the switch from science to the hobby that is very relaxing. We can't avoid failures in science, real failures which cannot be overcome otherwise than by taking a rest. For that small rest, the hobby is very important. So a hobby is, in my opinion, a necessity and I could have improved my research work by having a well defined creative hobby. Many colleagues suggested to me that the right procedure of living is to start with scientific work and then slowly switch over into administrative work. Most people do this. I would prefer to stay in science till my last day. Administration is definitely a field of its own. You have to love it, it is a full profession, it isn't even a hobby. Therefore, for the administrative directors of universities, specialists are used, and not amateurs who learned it on the side. They may make even with all the goodwill they have, mistakes by' the simple fact that administrative and economical problems are just as difficult, as any other scientific issue. If they are specialists, the universities need very few of them. But if they are amateurs, the universities overload themselves with administrators. There are some exceptionally bright colleagues who used administration as their hobby. But there are very few of them as far as I could see.

I would like, in, a new life, a private library already in early age. To own a book is very different than from borrowing a book. If I own a book, I read it and read it, and L really know the spirit of it. It is very seldom that I can get the spirit of a long book, even if I am permitted to borrow it for a few months. So I would spend all my income to have a library. Many people say that you really don't need books. You need maybe two books. In the United States, I was told that you practically need only one book: a checkbook. I am very sorry I do not go along with this concept. The human body just consists of two different things, the physiological and the mental part. And, unfortunately, the mental part needs many, many books.

Do you need many friends? I did not need many in my life, but I needed friends who were older than me. I travelled much and visited many different countries and I never will forget the pleasure of having kept a friendship with one Frenchman who was my teacher when I was 10 years old. As he became older and older, his letters became more and more deep. And when I was 60, he still was able to tell me things which were worthwhile to think about.

___________________________

GEORG VON BÉKÉSY CENTENARY MEETING

26 June, 8:30-11:00, Great Lecture Hall, 2nd floor

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Roosevelt tér 9

Ferenc Glatz, president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences:

OPENING

George Marx, president of the Hungarian Physical Society:

BÉKÉSY'S CULTURAL ROOTS AND HIS INTERDISCIPLINARITY

Jan Nilsson, president of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences:

BÉKÉSY IN SWEDEN

Daniel Carlton Gajdusek, Nobel laureate in medicine and physiology:

BÉKÉSY AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY

George Lajtha, from the Presidium of the Hungarian Electrotechn. Society:

R&D IN THE POSTAL LABORATORY

George Ádám, Hungarian Academy of Sciences:

HUMAN SENSES AND THE HUMAN BRAIN

László Kovács, College Szombathely:

BÉKÉSY IN HAWAII

Gábor Palló, Philosophical Institute:

BÉKÉSY AND THE ARTS

In case of interest, you are invited to the lectures and the exbibition

.___________________________________

Printed in the Fizikai Szemle in Hungarian in 1978/8 p. 281